One of the developments during the COVID-19 pandemic that, I must admit, I did not foresee was the rapid development of widespread resistance to mask mandates leading to their rapid politicization, with most of the resistance coming from the right. I should not have been blindsided; that I was surprised was a result of my not having been sufficiently aware of history, given that during the influenza pandemic of 1918 there arose similar resistance to masking and mask mandates, but, of course, in 1918 there was no mass media beyond newspapers and other publications, nor was there the Internet or social media. Of course, it wasn’t just resistance to masking that became an issue during the most recent pandemic; it was resistance to public health interventions in general, including mask mandates, restrictions on public gatherings, and, of course, vaccines. Of these, I realized that the antivaccine movement would quickly transfer its old misinformation, disinformation, tropes, pseudoscience, and conspiracy theories to the new COVID-19 vaccines, and so it did. However, it was broader than that. It was about public health, with resistance to vaccines being part of the entire package of resistance to other public health interventions, such as mask mandates, school closures, business closures, and restrictions on public gatherings.

Of course, COVID-19 was a novel organism when it spread from its initial outbreak in Wuhan, China to the rest of the world to become a pandemic. There were no vaccines, nor were there any effective treatments other than supportive care. For the most severely ill patients, treatment consisted of basically supporting the patient and treating the compilations, hoping to keep the patient alive as long as possible to allow the lungs and body to recover. However, the novelty of the virus did not mean that it was so completely novel and different from existing respiratory viruses that nothing we knew before about public health was applicable anymore. It was a respiratory disease, spread by respiratory droplets and aerosols. It was a coronavirus, and we knew a lot about coronaviruses, particularly given the close call we had with SARS in 2002-2003. There was a long and extensive public health literature and considerable experience in dealing with infectious respiratory viral diseases. In brief, it was not necessary to reinvent the wheel.

That’s why, while perusing my usual sources for knowledge, monitoring quacks and antivaxxers, and blog fodder, a study published on Friday in JAMA Health Forum, entitled US State Restrictions and Excess COVID-19 Pandemic Deaths. Some of the descriptions of the study were a bit…hyperbolic, for instance:

Others were more straightforward:

One thing that caught my eye about the study was that it is a single author study. This is a pretty rare thing these days. The other thing that caught my eye was that it was by an economist, Christopher J. Ruhm, although he is a health policy economist and the study did follow Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline for cross-sectional studies.

In the introduction, Ruhm basically says what I said above, just with references:

US states swiftly responded to the emergence of COVID-19 by implementing a variety of policies including initial emergency declarations, diverse forms of shutdowns and, later, mask and vaccine mandates. The initial actions were almost universal,1 but opposition to these measures quickly developed.2,3 This dissent spilled into the political arena where Republican governors and legislatures in multiple states limited the authority of public health officials and banned mask and vaccine mandates.4,5

Numerous studies have evaluated the impact of policies designed to mitigate the COVID-19 pandemic.6–8 Early analyses suggested that strong social distancing measures curtailed the initial spread of COVID-19,9,10 with evidence of interactive effects between public and private mitigation efforts.11 However, the specific modeling assumptions and design criteria of some of these studies have been questioned,3,12,13 and these analyses generally covered only the initial stages of the pandemic.

I can’t help but note that limiting the authority of public health officials has long been a goal of the antivaccine movement, dating back years before the pandemic. Indeed, several years ago, as measles outbreaks were popping up again as the result of low MMR vaccine uptake, Republicans in my own state tried to pass a bill that would have sharply limited the power of local public health officials to act during an outbreak, including their power to keep unvaccinated children out of school, an incident that I once sarcastically referred to as “make measles great again,” given that it happened early in the first Trump administration. In any event, during COVID-19, there was a stark difference between “red” and “blue” states in terms of mask mandates, “shutdowns,” and vaccine mandates.

This study specifically looked at seven state activity limitations passed early in the pandemic, including stay-at-home orders; restaurant, bar, leisure activity, primary school, and higher education closures; and restrictions on public gatherings, data obtained from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). In addition, three behaviors were examined, including the percentage of the population completing a primary COVID-19 vaccination series and the the percentage of days individuals stated that they always wore a mask outside their home. In addition:

The percentage of the analysis period during which all states required individuals to wear masks when outside of the home was calculated using information from Ballotpedia35; for the District of Columbia, data were from the IHME.34 Kaiser Family Foundation data36 were used to construct variables indicating whether state government or school employees were required to be vaccinated as of February 2022, whether there were school mask requirements, and whether there were prohibitions on government vaccine or school mask mandates.

Actual behaviors were also examined:

Three behaviors were examined. CDC vaccination data37 were used to calculate the percentage of the population completing a primary COVID-19 vaccination series. The percentage of days individuals stated that they always wore a mask outside their home (mask use) was obtained from IHME.34 Reductions in time outside the home compared with the prepandemic period (mobility reductions) came from Opportunity Insights.38

The time period chosen for correlating public health policies with excess death rates was chosen to be July 2020 to June 2022, because before July 2020 state restrictions and public health policies were very similar across all states; it was the summer of 2020 when policies started to diverge between “red” and “blue” states, as explained in the introduction:

An additional challenge is that initial COVID-19 exposure was concentrated in a small number of locations: primarily New York state, its surrounding states, and Massachusetts. These initial infection rates were probably largely idiosyncratic, reflecting factors such as having high population densities, being travel destinations, and making extensive use of public transportation.16–18 During this early period, policy variation across states was limited1 and the lethality of COVID-19 was especially high19 because medical professionals had little experience with and few tools available to treat severe COVID-19 infections. Consequently, studies containing data for the early pandemic period, such as those examining the overall performance of states20 or groups of policy responses,21 faced particular challenges. Reverse causation also may have been problematic given that states with the worst initial conditions were likely to have implemented the most restrictive policies.22 Moreover, restrictions were often introduced as packages, which made it difficult to disentangle specific policy effects.

And as documented in the discussion:

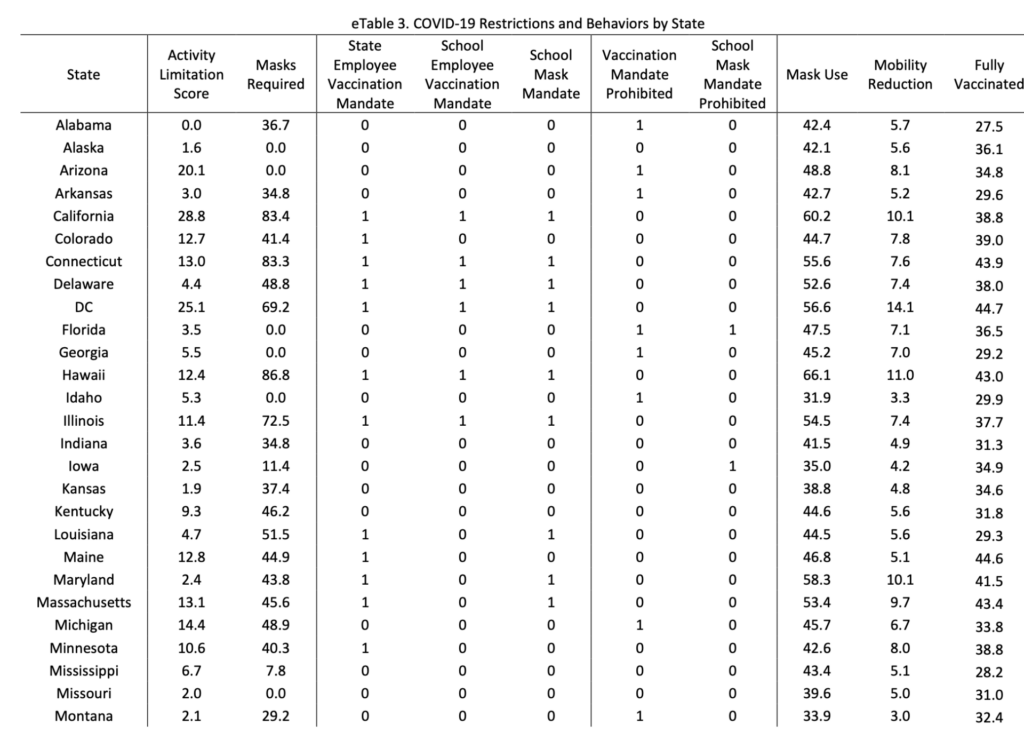

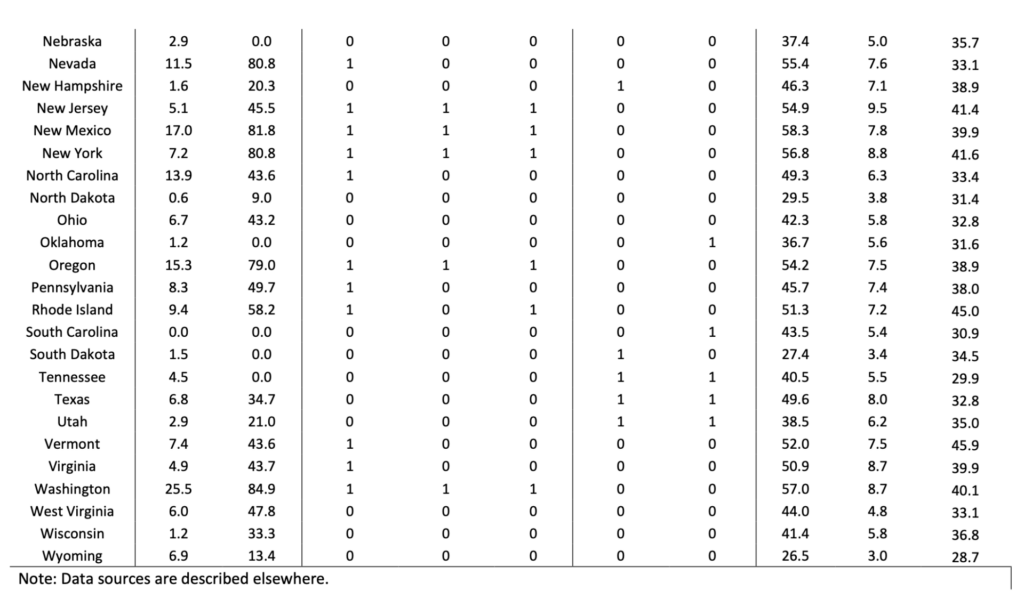

Considerable policy variation emerged in the second half of 2020, with states reducing or eliminating activity limitations and, somewhat later, mask requirements. Mobility reductions also declined rapidly during this period, as did mask use after the start of 2021. Vaccinations first became available in December 2020 and quickly became widespread, but with considerable geographic heterogeneity. Activity limitations had been essentially phased out by June 2021 and mask requirements by March 2022, at which point 23 and 11 states had instituted vaccination mandates for state and school employees, respectively, and 15 states had mandated masks in schools. Conversely, 13 states had prohibited vaccination mandates and 7 had outlawed school mask requirements (eTable 3 in Supplement 1).

I think it’s worth looking at eTable 3, just to see the variability between states in policies after July 2020:

That’s a wide array of public health interventions and a wide variability in what was permitted in various states. So how did this correlate to excess deaths? In brief, Ruhm began the analysis approximately 4 months after the first COVID-19 deaths in the US to mitigate what he describes as the “largely idiosyncratic variation at the start of the pandemic.” He then looked at excess deaths, age-standardized excess death rates per 100 000, and excess death ratios, using using state-level mortality and population data from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for 2017 to 2019 as baseline to compare the excess death rates from 2020 to 2022. Moreover, his primary analysis focused less on individual policies, but on packages of “weak” versus “strong” public health interventions, defined thusly:

Therefore, particular emphasis was placed on results for packages of weak and strong restrictions, where the former (latter) were calculated using population-weighted averages for the 10 states with the lowest (highest) overall restriction scores. Specifically, weak restrictions referred to activity limitation scores and mask requirements of 0.80 and 1.41 SDs less than the national average; no vaccine or mask mandates; and vaccine and school mask prohibition values of 0.79 and 0.75, respectively. Strong restrictions referred to activity limitation scores and mask requirements of 1.07 and 1.26 SDs, respectively, greater than the national average; universal school and state vaccination mandates and school mask requirements; and no vaccine or mask mandate prohibitions (eTable 1 in Supplement 1).

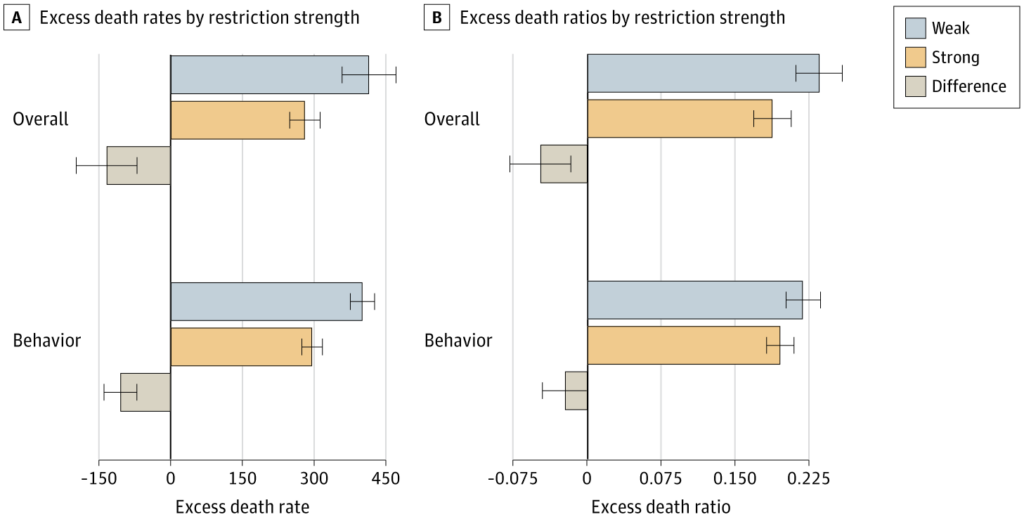

This brings us to the “money figure,” Figure 3:

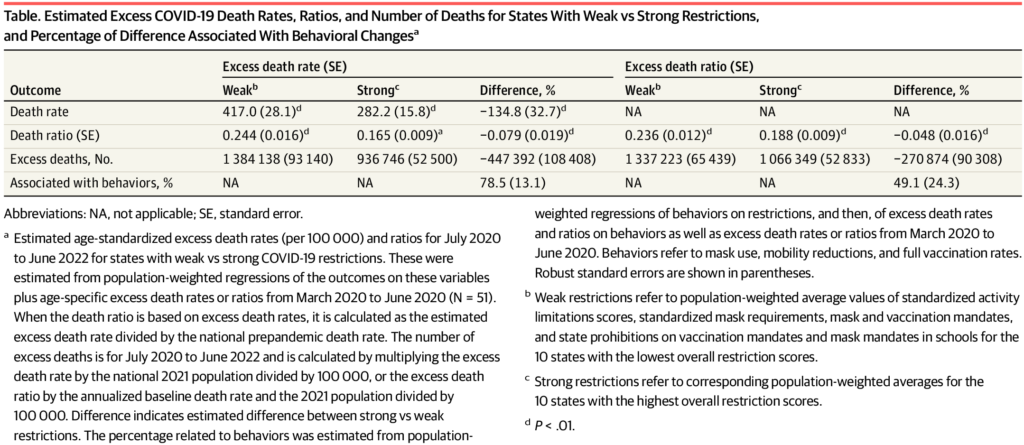

Continuing the analysis, Ruhm tries to estimate how many more people would have died if all 50 states had adopted the “weak” restrictions and how many lives might have been saved if all 50 states had instituted “strong” restrictions, leading to the second “money chart,” this table:

These analyses led the Ruhm to observe:

Using the primary specifications, the estimates suggested that if all states had weak restrictions, there would have been 1.3 million to 1.4 million excess deaths from July 2020 to June 2022, that is, 271 000 to 447 000 more than estimated with universal strong restrictions, a 25% to 48% difference (Table). Compared to the 1.18 million actual excess deaths over the study period, weak restrictions in all states would have resulted in an estimated 13% to 17% increase, and strong restrictions in a 10% to 21% decrease. Behavioral changes were associated with 49% to 79% of the overall restriction premia (Table and Figure 4; eTable 9 in Supplement 1).

Interestingly, not all polices were as strongly associated with higher or lower excess death rates, as Ruhm notes in the discussion, even as he correctly and emphatically points out that his study does not support the resistance view that COVID-19 public health interventions do not work:

These study findings do not support the views of those opposing COVID-19 restrictions who erroneously believe the restrictions did not work. To the contrary, the package of policies implemented by some states probably saved many lives. However, all restrictions were not equally successful. Evidence of protective effects was weakest for activity limitations. This may have partially concealed benefits at the start of the pandemic, before the analysis period, or reflected reverse causation given that most activity limitations were implemented before political considerations dominated, when states were likely to be especially responsive to local variations in infection rates.

I also note that Ruhm did not downplay or deny the potential costs of the public health interventions described, contrary to the caricature of public health advocates promulgated by those opposed to public health interventions as people who don’t give a rodential posterior about the harm caused by business and school closures, limitation of nonurgent care at hospitals, and the like. He even notes that “reductions were not necessarily sufficient to justify imposing restrictions because they also imposed a variety of costs,” pointing to harms to educational attainment caused by school closures, as well as harms in terms of financial loss and social isolation, particularly in nursing home patients, caused by “lockdowns,” even as he notes that harms from “loss of liberty” that can’t really be precisely valued. Being an economist, Ruhm couldn’t help but put things in more financial terms than I as a physician like, noting that “using value of statistical life estimates ranging from $4.7 million to $11.6 million,42,43 the estimated lives saved from strong (vs weak) restrictions over the 2-year period were worth $1.3 trillion to $5.2 trillion—6% to 22% of 2021 gross domestic product—providing a possible benchmark against which to evaluate this loss.”

Overall, to me this study is pretty strong evidence that longstanding public health science did not have to be reinvented at the beginning of the pandemic and that standard interventions for infectious viral diseases worked for COVID-19, no matter how much advocates of “natural herd immunity” and antivaxxers—but I repeat myself—try to argue otherwise. The study is not without weaknesses, obviously. No study is. For instance, this is a cross-sectional study and therefore can’t directly demonstrate causation, and the study design was at the state level, which meant that the study could not identify effects due to the polices of local governments. Also, since policies were often introduced as “packages,” it was difficult to assign importance to individual policies. Timing of policy implementation wasn’t always clear, either. Even so, I have to agree with Ruhm that his study is persuasive evidence that “strong COVID-19 restrictions saved lives and that the death toll was probably considerably higher than it would otherwise have been in states that resisted imposing these restrictions, banned their use, or implemented them for only relatively short periods of time.”

As I wrote this on Sunday, I was rather surprised at how little discussion I found regarding this study from the usual sources that I would have expected to be attacking it. I didn’t even find much on X, the hellsite formerly known as Twitter, where I would have expected to find a lot of the usual suspects piling on, trying to find any flaw that they could. The vast majority of the posts on X were either positive or just neutral postings of a link to the study and a story about it. It’s been two days since the study was published; that’s usually plenty of time for Brownstone Institute flacks, “Sensible Medicine” brave mavericks, and antivaxxers to have come up with long rants about how bad the study has. I don’t know whether the lack of such attacks means that they haven’t found a good attack yet or that, for some reason, they haven’t really noticed the study even though it was published in a JAMA journal. What I do know is that thesis yet more evidence that public health interventions work and that failure to adhere to them is associated with unnecessary death and morbidity.